Management Tool – Performance Quantification Framework

Quantification: the act of counting and measuring that maps human sense observations and experiences into members of some set of numbers

The problem with measuring performance

A common challenge of performance assessment is measuring both the magnitude of change in a person’s performance as well as the direction of that change.

For the purpose of our discussion, here are some quick definitions:

- Direction: Whether a person is getting better or not

- Magnitude: How much that person is getting better or worse

As the old saying goes, you can’t manage what you can’t measure. If you’re trying to get someone to improve at something, you need to be able to not only determine whether they are moving forward (or backwards), but also – and equally as importantly – by how much.

Someone running up your Slope of Expectations needs to be managed very differently than someone who is strolling up … or sliding down.

This is somewhat easily solvable for objective criteria. You can measure how many times a person broke an integration build, the number of times the infrastructure under management went down unexpectedly or whether a project was delivered within acceptable time, financial and quality thresholds.

The problem becomes quite tricky, however, for measuring behavioural criteria, which are generally subjective to begin with. For example, performance plans usually contain behavioural goals, such as demonstrating leadership, or one of my personal favourites: tenacity. I mean, how do you measure leadership or tenacity?

A Performance Quantification Framework

One solution to this problem is to put a framework around how to quantify, measure and record performance indicators, both outcome-based and behavioural. The foundational attributes of such a framework are:

- Relevance

- Definition

- Frequency

- Score

- Reasoning

Using these attributes in conjunction with other frameworks (such as the Craftsman Model), you can create a valuable mechanism to provide real insights into a person’s performance. You basically take each performance indicator for a given role at a career stage, and apply the attributes against it. While this might take a little bit of time up-front to set up, it will yield great benefits when you sit down do performance appraisals later.

Lets look at each of the attributes in detail.

Relevance

Carefully assess whether the metrics being measured make sense, both in general, and in your environment.

A lot of times I’ve found that these metrics exist because they’re a remnant of the past. Someone copied them from a self-help book they were inspired by, and the metric became embedded in the performance measurement process. That, or someone in management needed labels for check-boxes on the performance appraisal form and they thought tenacity was a good candidate.

If you find this idea amusing – it’s actually not. I’ve worked in places where I’ve had to provide examples of, and justify my tenacity in annual performance reviews. I can tell you its a mind-numbing task.

Definitions and guidelines

To be able to determine the magnitude of change, first you need to agree on the definition. This can be done by establishing clear guidelines and examples of what such behaviour looks like. For example, you could articulate what sort of things qualify as leadership for a given role, or what tenacity would look like.

It’s useful to get these examples publicised and validated by at least the senior members of your team. This doesn’t have to be a long, drawn out democratic process – part of being a good leader is to understand when autocratic decisions are appropriate. However, getting others involved allows the standards you’re setting to be externally validated and ratified.

Frequency

Figure out how often the desired behaviours need to be demonstrated in the appraisal period. This will partly depend on the role and an individual’s stage on their career path.

For example, you can decide that you don’t expect apprentices to show a lot of leadership. This doesn’t mean they may not do so – just that you recognise that they’re young in their career and will generally follow rather than lead. If they show leadership behaviour, then by all means it should be recorded and rewarded – that’s one of the ways to identify high performers for leadership grooming and succession.

Journeymen, however, are expected to demonstrate leadership as a sign of progression. For them, you can decide what leadership means, which behaviours exemplify it, and how often you would like to record it.

The other aspect is how well someone is doing at a particular point. If someone is under-performing, then obviously you have a problem and weekly (or sometimes even daily) measurements are relevant. For high performers who only need to be appraised quarterly, it might be a fortnightly or monthly measurement.

Also remember that making and recording observations requires an overhead in terms of time and effort. This is true in all systems – human or machine – and you’ll need to make a call about how much overhead you’re prepared to bear of your and other people’s time.

Score

This is can be fairly straightforward or as complex as you want to make it. My advice is to use a simple linear scale from +2 to -2. The negative numbers are required to record instances where the opposite of the desired behaviour was observed. An example of such a scale would be:

| Score | Description |

| 2 | Exceeded expectations, went above and beyond |

| 1 | Met expectations |

| 0 | Did not demonstrate expected behaviour |

| -1 | Showed signs of behaviour contrary to expectations |

| -2 | Clearly behaved against expectations |

The description of each scale gradation aren’t that important, as long as the general idea is understood.

Also, remember to keep it simple. It is quite appealing to extend the scale out both ways, or to do fancy things like make it non-linear. Don’t. Keep it simple, and focus on why the framework is being used rather than the framework itself.

Reasoning

When you record a score, always also record the reason that score was given. Again, this can be as short or as detailed as required. Depending on the frequency and the significance of the observation, I usually add enough detail to give me context and refresh my memory when I come back to it later.

One of the reasons for doing this is that it makes you think about the score you just gave. Sometimes I’ll record a score, write out the reasoning, and then realise that the score wasn’t really an accurate reflection of the commentary I’ve written.

Having comments is also useful when sitting down with someone to discuss their performance.You can have a more meaningful conversation when you are able to provide concrete examples of instances where you observed a behaviour that you want to encourage or discourage.

Similarly, if your environment requires it, these records are also helpful for formal human resource processes. For example, you might need to include evidence for justifying an extra performance bonus, or alternatively, to let someone go for consistent under-performance.

Add a pinch (or two) of discipline

A certain amount of discipline is required to consistently use this framework. There’s no point setting up the attributes for each performance indicator across your teams for each person if you’re not going to stick to using it.

Depending on how many people you need to do this for and how frequently, the best way to do this is to add timeslots and reminders to your calendar. All it then takes is perhaps two or three minutes – sometimes even less – to record a score and the reasoning for it.

Because your team is worth it.

Whoa! I hear you say. That sounds like a lot of work.

That’s right. No one said people management was easy. It’s a responsibility, and if you’re taking it seriously, you need to put a lot of hard work into it. Creating cohesive, engaged and high performing teams and a culture to support them requires a lot of effort. But that’s why you do it. That’s why it’s part of your craft.

I’ll write some more posts soon with examples of usage and the sorts of insights that can be extracted from using such a framework. In the meantime, I’d love to hear about any other tools and frameworks being used for quantifying performance.

Perspective

Syed’s blog is brought to you today by the word “Perspective”.

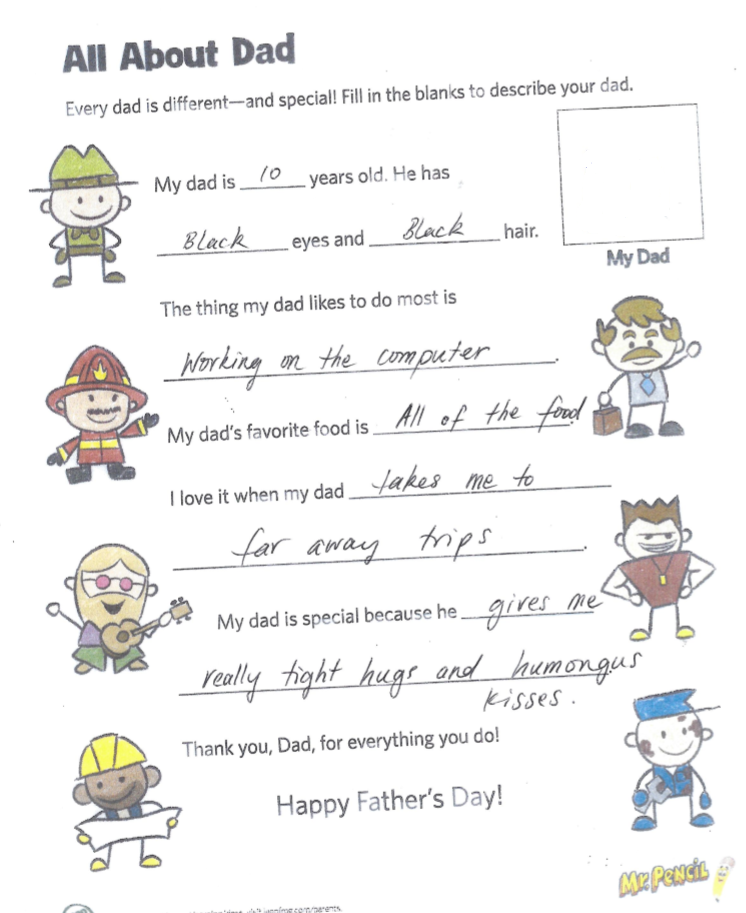

Lots of times, even when we know what’s important to us, it takes something external to give us perspective. With ever-connected, always-on, increasingly busy lives, we get lost in the day-to-day and forget to give the really important things in life their due. We get so caught up in our careers, in trying to be successful, that the little things that become big things slip by without noticing.

Like your kids.

So what triggered this post?

I’ve been away sick with a cold last week, so I left home yesterday morning knowing that there would be lots of work when I got into the office. On top of that, some unexpected issues had come up over the weekend, so those would also need to be looked at. Typical Monday morning, except on steroids.

Then, at 9:30, I got a call from my wife, saying that she had just been in a car accident. She was going out to drop my older son to pre-school, and unusually, had also decided to take the little two-year old with her. He’s also got a cold, so she thought she would take him to the doctor for a check-up after dropping the older one off.

As she pulled out of our driveway, a car came tearing down the street and smashed into her from her right, ripping the front bumper off.

Thankfully, no one was hurt.

After calming her down over the phone and dealing with the ensuing insurance process, I got her to take some photos of the damage to the car and send them to me.

It wasn’t until I saw the photos that it dawned upon me how close I had come to losing my family. If she had pulled out a second earlier, the other car would have ploughed straight into her and my two year-old at about twice the speed limit on our street.

Game over.

Perspective

Nothing I can do at work, no achievement, no success, no insights, no innovation can ever compare to the most important, precious thing in my life. My family.

I’m writing this as a reminder to myself (and hopefully to whoever else is reading this) that there are much more important things in life than work. When at work, be at work. Focus, be hyper-productive, kick goals, get it done. But don’t bring it home.

Keep it in perspective. Don’t let your hunger to get that big project over the line force you to sacrifice the really important little (or big) things in your life. Alternatively, if you have to deal with it at work, don’t bring any negativity back home with you and share it with your family.

I’ve been there. Done that. Put in 80 hour weeks. Worked and studied full-time simultaneously. Missed out on life. Looking back, I’m not glad that I did, but I’m trying to learn from it.

Remember what Stephen Covey said:

“Nobody on their death bed wished they’d spent more time at the office.”

Career lessons from riding motorcycles

After seeing how some people had learned invaluable life / business / leadership / parenthood / relationship lessons from The Godfather / Wesley Snipes / dogs / cats / horses / rocks (yes, you read that right), I thought I would write about some career lessons that I had learned from riding motorbikes.

In any case, I thought I would test my powers of abstraction and relate my love of motorcycle riding to a few career management lessons. Here are five, in no particular order.

And yes. That’s me on my Gixxer in the picture above. Pausing to reflect in a moment of enlightenment.

1. Ride because you enjoy it

There aren’t too many things that compare to the feeling that you get when you ride a motorbike. The rumble of the engine directly underneath you. The immediate, unadulterated feedback from the environment around you. The thrill of leaning into a curve. If you pay close attention, you’ll see most riders knowingly nod at each other as they go by on opposite sides of the road. Behind the helmets they’re smiling, because they know what fun the car drivers are missing out on.

Ride because you want to. Because its fun. Because you love it.

Career parallel

This equally applies to your career. Pick something you enjoy, that you love doing, and you’ll look forward to waking up in the morning and to the challenges that lie ahead. If you don’t, you wake up every day dreading what lies ahead.

This love also keeps you going when it gets tough. Much like riding when it’s stinking hot or pouring down, you’ll hit patches when work’s not too much fun or the pressure’s suffocating. Remember why you do what you do, and that the bad patch is only temporary. It will pass, and you’ll get to crank it on a clear strip once again.

2. Never stop learning

You never get to a point when you stop and say to yourself “I’m a perfect rider. I don’t need to learn anything else.” That’s because that can never be true. There’s always room for improvement. Good riders – especially smart, experienced ones – are always practising and looking at ways to improve their roadcraft skills.

Career parallel

Hippocrates summed it up at the beginning of the Aphorismi:

“Vita brevis, ars longa”

Life is short, and art long

It is commonly understood that Hippocrates was talking about art in terms of craft (as in craftsmanship). Constantly strive to get better. There’s always more to learn. Even when you think you’re a master.

3. Work your way up to a big bike

One of the main reasons for motorcycle accidents is people riding beyond their abilities. It takes times to learn and understand the dynamics of riding safely, and many people overestimate their skills. Figuring out and building the confidence to do things like braking hard and cornering at speed takes time, and unless you understand how to do it properly, results in accidents. Sometimes even death.

Start on a small bike that you can control, and learn your roadcraft. Then move to a bigger bike and keep learning.

Career parallel

I’ve seen lots of people in a hurry to build their careers, and they do it at a pace beyond their ability. Sure, you might be able to talk or lie your way into a role, but the crash at that speed will hurt. A lot.

Slow down. Get excellent at what you do. When you step up to the next role, it will be based on a solid platform of skills and insights.

4. Plan your route, but be ready for detours

I’ve had GPS Sat Nav in all my cars for about the last decade, so I’m used to kind of just following the instructions the nice lady with the American accent gives me. On a bike, however, it’s a completely different story. Although sat nav systems are readily available for motorbikes and of course my smartphone has the functionality, it’s not very easy to just look down at your device and poke at it with your armoured gloved finger and re-adjust. (You could, but you’ll most probably be plastered against the back of a bus shortly after.)

On a bike, you have to first figure out where you’re going, memorise the directions, and then off you go. If you get lost or encounter a detour, the best thing to do is work out the general direction you were originally heading in, and get back on track. (Ahhh … life before GPS.)

Career parallel

It’s unlikely that your career will also take a smooth, linear path. If you’re incredibly lucky, you might get an amazing mentor who might give you directions to make the right turns with enough notice. More likely, however, you’ll have to deal with lots of obstructions and hazards along the way – office politics, horrible bosses, back-stabbing co-workers, redundancies and an ever-changing world. If you’ve got a general direction in mind, though, you find it a lot easier to get back on track and keep moving towards you goals.

5. You’re responsible for your own safety

The common understanding among motorcycle riders is that you should ride like everyone is out to get you (specially taxis and courier minivans). When you first learn how to ride, they teach you about the safety bubble, how to buffer, look out for hazards and deal with various other road safety issues.

There are lots of drivers out there who are careless, negligent, impatient, psychotic, and otherwise general idiots – so much so that the term SMIDSY has now entered common parlance among riders. At the end of the day, though, how safe you are on the road is largely a function of how safely you chose to ride.

Career parallel

You’re responsible for your career. You might get lucky and work for a small founder run organisation with loving, caring people who are passionate and excellent at what they do.

If not, recognise that many people in the corporate world will choose to take advantage of you. From your colleague who manoeuvres for your next promotion off the back of your efforts to your boss who steals your ideas and steps on you for his, it’s up to you to protect yourself.

I’m not saying that everyone is like this, but the world is full of people who operate like taxi drivers – they’ll cut you off and do whatever it takes (ethical or otherwise) to get ahead of you.

As you can see, riding motorbikes can provide deep career insights as well as a fun mode of transport. What are some of the career lessons you’ve picked up from travelling on two-wheeled vehicles?