Feb 9, 2016 | Career, Management, Personal Development |

Don’t worry, this post is not about filling in household cracks or joinery gaps, but rather about gaps in organisations.

As a look back over my career so far, I must admit that I’ve followed a relatively linear path.

I worked in tech-support and enablement roles while I studied IT at university, became a software engineer, progressed through to IT architect roles and into Technology Management. While this trajectory has exposed me to a wide variety of ancillary disciplines, I haven’t had to make dramatic moves such as to Sales or Law.

However, one of the things I think that has immensely helped me along is the appetite to step in and solve problems around me, regardless of whether they were included in my job description or indeed had much to do with my direct role objectives. In effect, the propensity to fill the gaps.

Gaps are everywhere

All too often – especially in large organisations that are configured along specialised value chain silos – people become fixated with only their particular role. This can be driven by many factors: departmental politics, penalising cultures, an over-emphasis on KPIs. The end result, however, is that there often emerges a “gap” between people’s functions that no one is willing to fill.

This in turn leads to some remarkably unfortunate – although predictable – behaviour, manifested in things such as “passing the buck”, “finger pointing”, and “shifting blame”. People get defensive, collaboration pretty much dies and significant amounts of energy gets spent in setting up DMZs to conduct “hand-overs”.

Sometimes the gaps occur not between departments but within them, especially in project teams. Usually manifested as team dysfunction, this can be observed either in new teams that are going through their forming or storming phases, or even in well-established teams that are under immense pressure or on a death march.

Be the Gap Filler

Yes, it may not be in your job description. Yes, it may mean having some awkward conversations with people that you may not like and who probably don’t like you (at the moment). Yes, it may mean that you have to do some extra work. And yes, it may all be terribly boring.

But just like the little boy who saved Holland by sticking his finger in the dike, you will become the person who makes the most tangible difference.

It may not feel like it at the time, but people will notice. Your manager will notice, and appreciate you for it. Things will start working. Communications will get easier. Crises will become opportunities. When you need help, people will remember and help you. And if you’re aspiring to move into management, here’s a key: good management is about taking on the hard problems no one else wants to solve, and some of the most difficult ones are ones which involve gaps.

So assess the situation, determine where the biggest gaps are and go fill them.

Jun 20, 2014 | Management, Publications |

CIO Australia magazine recently reached out and asked what were some of the things to avoid when hiring, and published my thoughts online. There were some great responses, and here is the excerpt containing my mine.

Scenario

The scenario was this:

The CIO is planning to tap into data and analytics to help grow the organisation, and needs to add to the team to execute and complete projects.

The CIO hands over a job description to a recruiter to source a data scientist or data analyst, an “IT resource needed for big data projects who has at least five years’ experience in working in this type of role and has a master’s degree in data analytics”.

The recruiter has a ‘tick-off’ list but cannot find an ideal candidate who ticks all the boxes. Nine months down the track, the organisation still has not found a suitable candidate, with the CIO feeling like his or her only option may be to outsource the role.

What could be wrong with this situation?

My thoughts on hiring

I usually hire on potential rather than hard skills. Someone with at least five years’ experience in a nascent field is going to be hard to find anyway, so I would look for transferable skills such as problem solving or pattern analysis.

What you’ll find is people who come from traditional BI sort of space, who have reinvented themselves.

However, it’s a significantly different mindset to do big data type analysis versus doing traditional BI analysis. They are very different things, because they start from different points. One’s more exploratory and the other one is based on having a well understood set of parameters that you investigate.

There are parallel fields that lend themselves well to this sort of skillset – people who have a masters or a PhD in mathematics or propositional logic and that sort of stuff. You can tap into that sort of skillset.

It’s about how much time you want to invest in bringing them up to speed with commercial realities. What you really may want is someone with the core ability to attack a certain type of problem. Everything else you can polish around that.

I also wouldn’t necessarily start by looking for someone to fill the role directly if I didn’t understand it deeply first. My approach would be to engage a specialised consulting service to deliver two outcomes: set up the data analytics practice or framework, and then assist me in recruiting the right person to fill the role.

That way the consulting service, that I would ensure has expertise in data analytics, has assessed the maturity required to deal with the problem in my organisation, and can provide advice on what specific skills are required. They usually have a much better network of skilled professionals due to their focus or specialisation.

If engaging a consulting service was not an option, I would reach out to my personal network to source the data analyst.

If it was me, I wouldn’t write the job description for a data analyst by myself – I’ve been off the tools for so long so I wouldn’t know what to say technically. If you want to attract the right sort of people then you have to speak their language.

I don’t necessarily write job ads for developers or engineers, my teams helps re-write them because they understand what is current in the marketplace and what attracts the right sort of people.

Your thoughts on hiring

Do you contribute to recruitment in your organisation, and what sort of challenges do you face? Join the conversation in the comments here or on the CIO Australia website.

Jun 12, 2014 | Events, Leadership, Management, People Management |

As always, I continue to be amazed by my kids’ abilities to teach me lessons by forcing me to think about behaviours – theirs, mine, and people’s in general.

A lesson in the wild

This one came about during a recent camping trip. Hamzah and I camped overnight at the beautiful Bents Basin Campground, where we spent the day walking around trails and exploring the area. The next morning as I was preparing breakfast, Hamzah asked if he could have an Up&Go first. As I gave it to him, I asked him to sit down and pay extra special attention while he drank it. I told him that if he spilled it over himself we wouldn’t have a spare set of clothes for him to change into.

Now I know that he’s only 5 (or 5 and a half as he likes to correct me) and doesn’t really have the ability to sit quietly and drink out of a straw from a milk pack while actually wanting to run around with his friends, but hey, I can try, right?

As I finished cooking the eggs and toast, I went over to check how he was doing and found him sitting very quietly. When I squatted down, his eyes were full of tears and he said “send me to the naughty corner Baba”.

At first I didn’t understand. But when he repeated that he should be sent for a time-out as punishment, I noticed that he had (almost predictably) spilt a little milk on himself. As I smiled, gave him a big hug and wiped the tears (and spilt milk) away, it struck me how important it was to him to try to do what he thought was the right thing.

I hadn’t threatened him with punishment or even pressed the importance of not spilling the milk on him, merely made a passing comment as I had handed him the pack. Yet, he felt his mistake was bad enough to be disciplined, that he had let me down in a major way.

This was interesting. What was the reason for him to not only recognise that he had done something wrong, but to also ask to be sent to the naughty corner? Was it the thought of having disappointed me? Was it the intrinsic recognition that he had made a mistake?

This got me thinking about something I had heard a few days earlier …

An example from the business world

I recently attended an AGSM Alumni event on Customer Centricity, hosted by Dr Linden Brown, author of ‘The Customer Culture Imperative’. Also on the panel were John Parkin – Director of Customer Enablement, Telstra, John Stanhope – Chairman (nonexecutive), Australia Post, Professor Adrian Payne – Professor of Marketing, Australian School of Business, UNSW, and Dr Judith MacCormick, Partner, CEO and Board Practice, Heidrick & Struggles.

It was an excellent session, and is well worth listening to the audio recording as the panel discusses how to build strong, adaptable and innovative customer-centric cultures.

One of the insights from the panel discussion was that customer centricity depends on highly engaged employees. Dr Brown related a story from one of his case studies about Zane’s Cycles, where the store had agreed to put a purchased and decorated bicycle in the store’s display as part of a customer’s Valentine’s Day gift. For some reason, the bicycle wasn’t put on display, resulting in a very upset customer.

The rest of the story about how the business handled the situation is exemplary, and resulted in a happy outcome for both the business and the upset customer. However, one of the incredible parts of the story that stuck with me was the store employee who had been responsible for putting the bicycle in the store display recognised his mistake, and voluntarily wrote out a cheque for $400 to the store as compensation for the incident. To me this was an example of an employee who was so engaged that he volunteered to be (financially) disciplined.

Here is the 3-and-a-bit minute video of Chris Zane – owner of Zane’s Cycles – talking about the event and how it unfolded. Well worth watching.

Creating strong engagement

I had a think about both these situations with Hamzah and the bicycle store employee, and how people get to the point where they are completely engaged. I can’t comment on the culture at Zane’s Cycles since I haven’t experiences it first-hard, but there are plenty of articles and videos on the internet discussing how they operate. I also recognise that Hamzah is only a child, and my child at that, so there is a certain amount of influence that filial piety plays in that situation.

However, I’ve also observed this sort of engagement in my own teams, and here are some of the things that I believe can help create an environment that supports it.

Have clear and genuine values

Everyone, including organisations, have values, whether they explicitly recognise them or not. The important step in creating engagement is to be clear about what these values are, and why they are important to you. In addition to this, you really need to live these values – to lead from the front, so to speak. When people believe in your values and see you living and breathing them, they will usually follow.

Provide people the freedom to make their own mistakes

This is about empowering people and giving them the latitude, respect and encouragement to try whatever path they want to take to get to the goal. Needless to say, this must be within reasonable boundaries and in congruence to the values discussed earlier. I’ve found that if you give people responsibility, trust in their abilities and provide a safe environment to fail, they intrinsically become committed to “going the extra mile”.

Don’t sweat the small stuff

Finally, remember that everyone makes mistakes. I make them all the time. If the mistake is genuine (i.e. not deliberate) and can be recovered from without too much effort, sometimes it’s better just to let it go. People remember this and give you emotional credit for it, and when the time comes around where extra effort is required, they will put it in without being prompted.

Creating a culture that promotes strong engagement is a long-term and complex endeavour based on leadership and insights. What have you found that works for you?

May 6, 2014 | Events, Management |

Note: A

version of this post was published on the CIO Australia website (http://www.cio.com.au) on 16 April 2014.

The AGSM kicked off this year’s Learn@Lunch series on 19 February 2014 with an enticing question:

The question was being asked by David C. Thomas, PhD, who is currently Professor of International Business in the School of Management at the Australian School of Business, University of New South Wales. An accomplished academic, he is also the author of eight books, including … wait for it … Cultural Intelligence: Living and Working Globally.

Cultural Intelligence explained

Dr Thomas defines Cultural Intelligence as one’s ability to deal effectively with the cultural aspects of their environment. This important because as we become increasingly globally interconnected, we need to interact more and more frequently with people of other cultures. It is impossible to understand all cultures, and indeed to even comprehend more than a few (except superficially). As Dr Thomas points out, many well rounded, socially and emotionally intelligent people struggle with cross-cultural interaction.

The good news however, is that Cultural Intelligence can be developed using three interrelated elements: Knowledge, Skills and Mindfulness.

Knowledge

This element of Cultural Intelligence is about understanding what culture is. At minimum, it is an abstract understanding of the concept of culture – as in being aware that others may be culturally different to oneself. In practice, it means having working knowledge of the details and nuances of the particular culture one needs to interact with. It also requires the ability to distinguish between personal behaviour and societal norms.

Skills

These are the behavioural meta-skills needed to become more culturally intelligent:

- Perceptual Acuity – sharpness of perceiving details around you

- Empathy – the ability to understand and share the feelings of another

- Tolerance for ambiguity

- Relational Skills – being able to relate to others

- Adaptability

As you become more competent at these, you can select which ones to use in a situation requiring cultural tact.

Mindfulness

Finally, this is the mediating step that links knowledge with skills. It is essentially the opposite of mindlessness, where you are simply unaware of your cultural context. It lets you stop, take account of the situation you’re in, recall the knowledge about your context, and then apply your behavioural meta-skills to behave in a culturally appropriate way.

An interesting example: Carlos Ghosn – A (culturally) smart cookie

One of the more fascinating examples of someone with high Cultural Intelligence Dr Thomas gave was Carlos Ghosn, the President and Chief Executive Officer of Nissan Motor Co., Ltd. Ghosn is a French-Lebanese-Brazilian who is largely credited with one of the most dramatic downsizing and turnarounds of a major organisation in the modern business era. What’s even more fascinating is that he runs this massive multi-national by splitting his time evenly between Tokyo and Paris, both places steeped in distinct, rich cultures and business customs.

Ghosn’s management style is frequently described as cross-cultural, and he credits his ability to navigate between cultures as one of his strengths. In his CEO message on the Nissan Global website he points out that cultural diversity can create a competitive advantage, saying that “solutions come from using the talents of both men and women, young and old, from all levels in the organization or from different cultures.”

He even has his own superhero comic book series. That’s right – “The True Life of Carlos Ghosn”. (I’m trying to imagine a comic book based on my life. Probably wouldn’t be as exciting.)

Experiencing different cultures

The lecture really resonated with me since I have worked in a number of situations that have required interacting with people with different cultural backgrounds, and reflecting on those situations makes me realise how important cultural intelligence really is.

Local interactions

One of the things I love about living in Sydney is the exposure and ability to interact with a plethora of cultural backgrounds. I’ve been privileged to work in a number of organisations where many of my colleagues had different ethnic backgrounds and upbringings. This also provides some interesting challenges.

For example, I once worked with a number of Japanese colleagues for a couple of years. It was my first time interacting closely with people of Japanese background, and I remember getting very frustrated. We would spend lots of time in deep and intense discussions, which would mostly end in what I thought was an agreement. Later, I would find out that they would renege on that agreement or deny having reached it at all.

After a few of these events, it occurred to me that the reason for this misunderstanding was largely cultural: when they nodded during our discussions, they were just being polite and letting me have my say. Whereas I had taken their nods to mean acceptance, they were simply nodding in acknowledgement of having heard my point of view.

Once I realised this, I had to change my approach to incorporate this cultural understanding. I re-framed the conversations to try to get their points of view out without trying to push mine first, and making sure at any agreement we reached as actually explicitly acknowledged as such.

Remote interactions

Working for a global companies is also an interesting exercise in cultural awareness, where many of your colleagues are from and located in different parts of the world. Not only are they from a different culture, they are in a different culture and of course behave within its norms.

Being culturally intelligent can be very helpful here, not only to foster strong relationships across the organisation, but also to be effective in your job if it requires frequent cross-regional interactions.

For example, when rolling out changes to business processes or technology systems, it can really help to be aware of how different cultures react. I’ve found that changes are better implemented via mandate in certain parts of the world, while others require more of a co-opting approach.

Organisations as Cultural Containers

While not quite the idea that Dr Thomas was talking about, each organisation has its own unique culture as well. I’ve worked in a large variety of organisations, from two person to 10,000 strong consulting firms, government departments, financial services institutions and global system integrators while covering a wide range of industries. While industry norms exist, company culture usually varies significantly between organisations of the same size in the same market. Many of the ideas discussed in the lecture can be adapted to a micro-level and used to intelligently navigate the culture within the specific place you work at.

Takeaways

All this made me think about how real this is as an actual, practical concept, not just an academic one. Certainly in Australia, the importance of being able to effectively interact with our neighbouring countries has recently gained much prominence. This is highlighted in publications such as Australia in the Asian Century, which was mentioned by both David Thodey as well as Andrew Stevens, and also discussed by Professor Joseph Cheng.

In the end, however, the best reason to develop your Cultural Intelligence is to be able to more effectively deal with people of other cultural backgrounds. As Stephen Covey said, “seek first to understand, then be understood“.

Nov 7, 2013 | Management, People Management |

In an earlier post, I talked about using performance appraisals as a tool to have a personalised, growth-focussed conversation with people about their careers within the context of your organisation’s business operating environment.

It is important to ensure that these conversation are well grounded in the opportunities available and the established career paths you have set up for your teams.

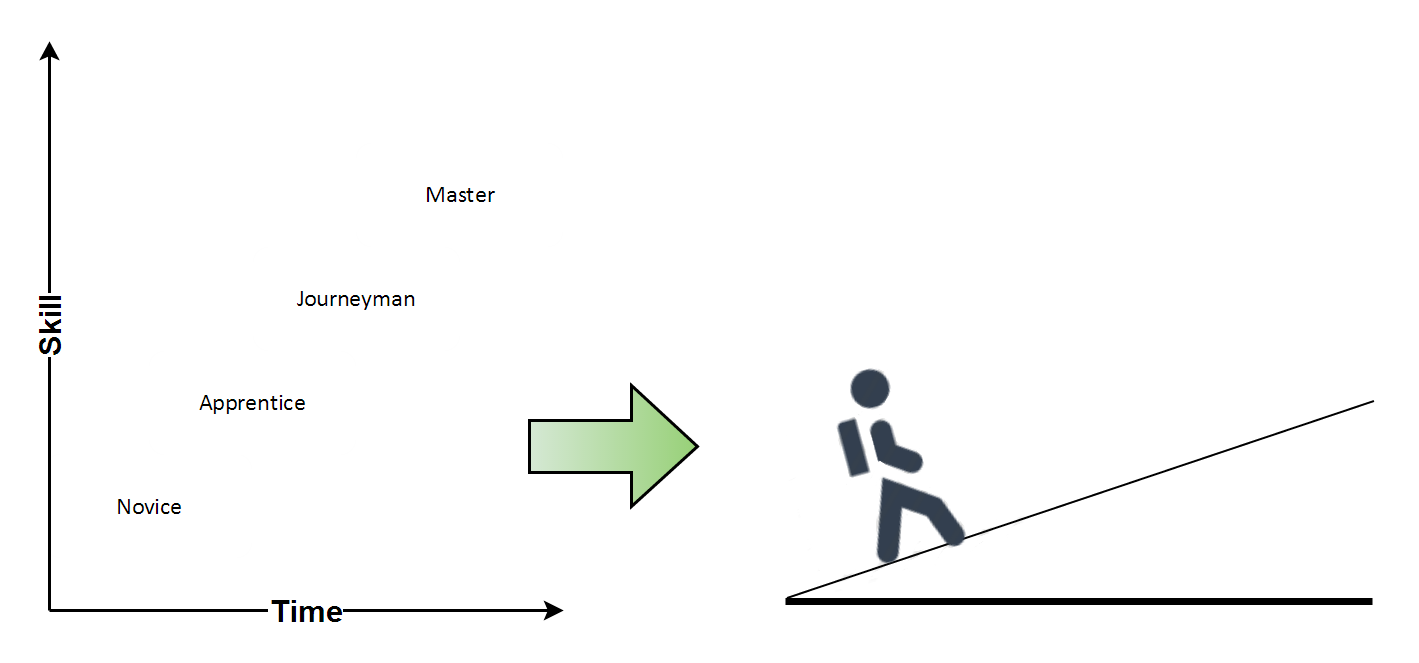

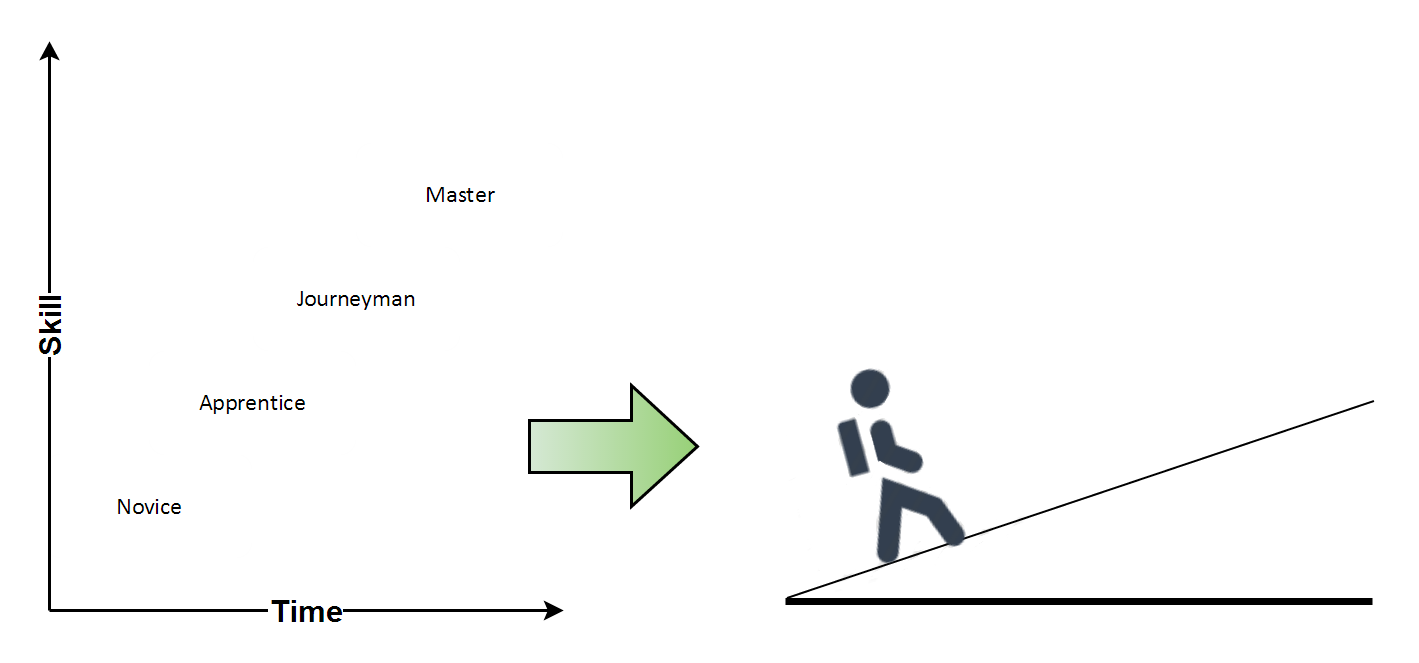

One of the ways I have done this is by adapting the Craftsman Model for Career Management to create a tool that I call Syed’s Slope of Expectations:

It essentially takes the stages along the craftsman journey and plots them on a linear slope, outlining the path one needs to follow to move forward in their career. Remember that this is a model, so it necessarily (over)simplifies things to allow focus on a particular area of analysis.

One of the reasons this works well is that it easy to understand. Everyone gets the metaphor, and it doesn’t require lots of planning or documentation to start using it. You can go out for a coffee and use it to have a casual chat while waiting in in queue for your slightly hot organic weak decaf skim soy caramel latte with extra froth.

How it works

Basically, it can be used to have conversations with individuals and explore one or more of the following:

- Where on the slope they currently are.

- Have they moved on the slope?

- Which direction they’re moving in (or standing still).

- Why do they feel they’re moving in that direction?

- What needs to happen to keep moving forward (or stop sliding back)?

- Is this still the right slope from the last time we spoke?

- If this is the wrong slope, how do we get them to the right one?

This isn’t an exhaustive list. Use these as starting points and go from there. This is an analysis tool, so make sure you ask lots of open-ended and probing questions in a non-interrogative way.

Although it isn’t essential, it also helps to have some sort of career progression framework in place to refer to when having these conversations.

It’s all in the name

When I first called it “Syed’s Slope of Expectations”, it was deliberately meant to be a joke. Everyone chuckled when I first drew it up in a group-wide meeting and explained how it works. But the name has interesting connotations:

The expectations are mine

Potentially the more accurate name is “The Slope of Syed’s Expectations”, since I expect people to put in their best effort at work. If they don’t, then they let themselves, the rest of the team, and the organisation down, and I really want to understand why so I can help them get over it.

It’s an incline

Climbing up, by definition, is challenging. If someone isn’t being challenged, they’re not growing and getting better. Not a good thing. It’s understandable that everyone goes through periods where they just need to consolidate their skills or are going through a major life event outside work. Other than that, they really need to be ploughing ahead.

If you’re not going forward, you’re standing still or sliding down

I really like it when someone identifies themselves in this situation. It requires a keen sense of awareness and contextual understanding, and tells me that I need to invest more time to help this person out. We can explore why a person is feeling this way, whether their perception is just based on some short-term frustration or an actual issue, or how we can find ways to remove impediments from their path.

It’s really about communication

Communication is one of the foundational elements of great people management. Hopefully this tool helps improve yours as you move along your path to becoming a management and leadership master.

I’d love to hear if you use a similar concept, and what your experience with it has been.

Nov 1, 2013 | Career, Management |

Performance appraisals are generally uncomfortable events.

Not just when its my performance that is being reviewed, but also when I’m doing the reviewing. Having said that, I recognise it as an integral part of people management, and without such evaluations it would be impossible to help people develop and move forward in their careers.

Facilitating great business outcomes while enabling people to do interesting, meaningful and challenging work is essentially is what people management is about. If you can focus the conversation on how to progress someone’s career rather than what they’ve done well or otherwise, you actually have a shot at engaging them.

Engagement – one of the ultimate management goals – leads to discretionary effort.

Discretionary effort is what people choose to put into an activity, above and beyond what they are required to.

So how does one go about making performance appraisals a more comfortable event, which can in turn bring about more engagement? Here are some ways that I find helpful.

Not an annual event.

For starters, make the frequency contingent on how much support your staff need to get where they and you want to get to. Some people need lots of discussion and help, some just need little nudges. Figure out where they’re at, agree to a cadence, and stick to it.

Even if you catch up with them once a quarter, it feels a lot less burdensome than a massive career chat once a year.

Also important to note is this is only the committed schedule. If you or they feel like they are going through a challenging situation or are undertaking a stretch assignment, make time to give them extra attention.

Remove the formality.

Make the conversation as informal as you can. A performance appraisal should be a two-way conversation – meaning both parties need to be relaxed and comfortable speaking their minds for it to be effective. Generally this can’t happen in a rigidly formal setting.

If you can do it outside your office, great! If you can do it over coffee, even better. It breaks the ice and turns it into a friendly chat rather than an assessment.

If you need to sit in your office behind your desk in an authoritative position to feel confident, then perhaps you should re-think your career in people management.

Focus on them.

The best way to engage anyone is to answer the WIIFM (What’s In It For Me?) question for them. Most people I review don’t ever explicitly ask it, and its obvious some have never actually even thought about it. It is however quite helpful to frame the conversation around this so it becomes about them, their career path and their growth rather than a box-checking exercise.

Obviously, all of this has to occur within the context of your business operating environment and your team’s long and short term goals. There’s not much value dwelling on someone’s aspirations to become a world class, full time acrobat in a travelling circus if their primary role at work is project manager.

Use failures as lessons learned.

As I mentioned earlier, the best way to deal with failures and setbacks is to learn from them. A lack of failures and setbacks means someone isn’t really trying to push themselves out of their comfort zone.

Within reason and accepted thresholds, accept and appreciate risk-taking and failures, and provide a safe environment for people to do so. Really interesting and innovative ideas start to surface when people’s constraints are removed and they feel that their manager has their back.

Use weaknesses as opportunities.

Pointing out someone’s weaknesses – even if they are aware of and acknowledge them – isn’t very motivating. Instead, use the issue to have a conversation about the importance of addressing the weaknesses, what potential obstacles may be causing or exacerbating them, and what the path to improvement could be.

Framing the issue this way enables you to change the conversation from one where someone has to defend themselves to one where they are interested in exploring how to get better.

Be honest and transparent.

This goes without saying, but as the old proverb goes, “honesty is the best policy”. If you use lies and deception to extract performance out of people, you will eventually get found out, and the resulting disengagement and resentment will come back to bite you.

If career progression opportunities exist, are real, and are achievable, then that’s great. If they don’t, then do the right thing and let people know.

There are, of course, sensitive matters that you may not be able to fully disclose. Barring those, the more information you can provide to people, the better decisions they (and you) can make. Sometimes those decisions will result in them leaving, but that’s usually a good outcome for everyone involved.

Ask for feedback.

There’s not much point trying to get better at something without getting feedback about it. Apply the same principle to yourself, and get feedback about how the appraisal process feels and works (or doesn’t) for everyone else.

If you’ve made the effort to genuinely help others, given them time and attention, and acted honestly and transparently, most people will trust you and reciprocate with real feedback to improve the process – and your skill at implementing it.

So there it is. Certainly not a comprehensive list, but some of the ways I’ve found to make the conversation more meaningful and effective. Done the right way, performance appraisals can actually be something you and your staff can look forward to.

What are your strategies to making the performance appraisal process better?