Jun 12, 2014 | Events, Leadership, Management, People Management |

As always, I continue to be amazed by my kids’ abilities to teach me lessons by forcing me to think about behaviours – theirs, mine, and people’s in general.

A lesson in the wild

This one came about during a recent camping trip. Hamzah and I camped overnight at the beautiful Bents Basin Campground, where we spent the day walking around trails and exploring the area. The next morning as I was preparing breakfast, Hamzah asked if he could have an Up&Go first. As I gave it to him, I asked him to sit down and pay extra special attention while he drank it. I told him that if he spilled it over himself we wouldn’t have a spare set of clothes for him to change into.

Now I know that he’s only 5 (or 5 and a half as he likes to correct me) and doesn’t really have the ability to sit quietly and drink out of a straw from a milk pack while actually wanting to run around with his friends, but hey, I can try, right?

As I finished cooking the eggs and toast, I went over to check how he was doing and found him sitting very quietly. When I squatted down, his eyes were full of tears and he said “send me to the naughty corner Baba”.

At first I didn’t understand. But when he repeated that he should be sent for a time-out as punishment, I noticed that he had (almost predictably) spilt a little milk on himself. As I smiled, gave him a big hug and wiped the tears (and spilt milk) away, it struck me how important it was to him to try to do what he thought was the right thing.

I hadn’t threatened him with punishment or even pressed the importance of not spilling the milk on him, merely made a passing comment as I had handed him the pack. Yet, he felt his mistake was bad enough to be disciplined, that he had let me down in a major way.

This was interesting. What was the reason for him to not only recognise that he had done something wrong, but to also ask to be sent to the naughty corner? Was it the thought of having disappointed me? Was it the intrinsic recognition that he had made a mistake?

This got me thinking about something I had heard a few days earlier …

An example from the business world

I recently attended an AGSM Alumni event on Customer Centricity, hosted by Dr Linden Brown, author of ‘The Customer Culture Imperative’. Also on the panel were John Parkin – Director of Customer Enablement, Telstra, John Stanhope – Chairman (nonexecutive), Australia Post, Professor Adrian Payne – Professor of Marketing, Australian School of Business, UNSW, and Dr Judith MacCormick, Partner, CEO and Board Practice, Heidrick & Struggles.

It was an excellent session, and is well worth listening to the audio recording as the panel discusses how to build strong, adaptable and innovative customer-centric cultures.

One of the insights from the panel discussion was that customer centricity depends on highly engaged employees. Dr Brown related a story from one of his case studies about Zane’s Cycles, where the store had agreed to put a purchased and decorated bicycle in the store’s display as part of a customer’s Valentine’s Day gift. For some reason, the bicycle wasn’t put on display, resulting in a very upset customer.

The rest of the story about how the business handled the situation is exemplary, and resulted in a happy outcome for both the business and the upset customer. However, one of the incredible parts of the story that stuck with me was the store employee who had been responsible for putting the bicycle in the store display recognised his mistake, and voluntarily wrote out a cheque for $400 to the store as compensation for the incident. To me this was an example of an employee who was so engaged that he volunteered to be (financially) disciplined.

Here is the 3-and-a-bit minute video of Chris Zane – owner of Zane’s Cycles – talking about the event and how it unfolded. Well worth watching.

Creating strong engagement

I had a think about both these situations with Hamzah and the bicycle store employee, and how people get to the point where they are completely engaged. I can’t comment on the culture at Zane’s Cycles since I haven’t experiences it first-hard, but there are plenty of articles and videos on the internet discussing how they operate. I also recognise that Hamzah is only a child, and my child at that, so there is a certain amount of influence that filial piety plays in that situation.

However, I’ve also observed this sort of engagement in my own teams, and here are some of the things that I believe can help create an environment that supports it.

Have clear and genuine values

Everyone, including organisations, have values, whether they explicitly recognise them or not. The important step in creating engagement is to be clear about what these values are, and why they are important to you. In addition to this, you really need to live these values – to lead from the front, so to speak. When people believe in your values and see you living and breathing them, they will usually follow.

Provide people the freedom to make their own mistakes

This is about empowering people and giving them the latitude, respect and encouragement to try whatever path they want to take to get to the goal. Needless to say, this must be within reasonable boundaries and in congruence to the values discussed earlier. I’ve found that if you give people responsibility, trust in their abilities and provide a safe environment to fail, they intrinsically become committed to “going the extra mile”.

Don’t sweat the small stuff

Finally, remember that everyone makes mistakes. I make them all the time. If the mistake is genuine (i.e. not deliberate) and can be recovered from without too much effort, sometimes it’s better just to let it go. People remember this and give you emotional credit for it, and when the time comes around where extra effort is required, they will put it in without being prompted.

Creating a culture that promotes strong engagement is a long-term and complex endeavour based on leadership and insights. What have you found that works for you?

Dec 6, 2013 | People Management |

Quantification: the act of counting and measuring that maps human sense observations and experiences into members of some set of numbers

The problem with measuring performance

A common challenge of performance assessment is measuring both the magnitude of change in a person’s performance as well as the direction of that change.

For the purpose of our discussion, here are some quick definitions:

- Direction: Whether a person is getting better or not

- Magnitude: How much that person is getting better or worse

As the old saying goes, you can’t manage what you can’t measure. If you’re trying to get someone to improve at something, you need to be able to not only determine whether they are moving forward (or backwards), but also – and equally as importantly – by how much.

Someone running up your Slope of Expectations needs to be managed very differently than someone who is strolling up … or sliding down.

This is somewhat easily solvable for objective criteria. You can measure how many times a person broke an integration build, the number of times the infrastructure under management went down unexpectedly or whether a project was delivered within acceptable time, financial and quality thresholds.

The problem becomes quite tricky, however, for measuring behavioural criteria, which are generally subjective to begin with. For example, performance plans usually contain behavioural goals, such as demonstrating leadership, or one of my personal favourites: tenacity. I mean, how do you measure leadership or tenacity?

A Performance Quantification Framework

One solution to this problem is to put a framework around how to quantify, measure and record performance indicators, both outcome-based and behavioural. The foundational attributes of such a framework are:

- Relevance

- Definition

- Frequency

- Score

- Reasoning

Using these attributes in conjunction with other frameworks (such as the Craftsman Model), you can create a valuable mechanism to provide real insights into a person’s performance. You basically take each performance indicator for a given role at a career stage, and apply the attributes against it. While this might take a little bit of time up-front to set up, it will yield great benefits when you sit down do performance appraisals later.

Lets look at each of the attributes in detail.

Relevance

Does this performance indicator make sense?

Carefully assess whether the metrics being measured make sense, both in general, and in your environment.

A lot of times I’ve found that these metrics exist because they’re a remnant of the past. Someone copied them from a self-help book they were inspired by, and the metric became embedded in the performance measurement process. That, or someone in management needed labels for check-boxes on the performance appraisal form and they thought tenacity was a good candidate.

If you find this idea amusing – it’s actually not. I’ve worked in places where I’ve had to provide examples of, and justify my tenacity in annual performance reviews. I can tell you its a mind-numbing task.

Definitions and guidelines

A clear understanding of the performance indicator.

To be able to determine the magnitude of change, first you need to agree on the definition. This can be done by establishing clear guidelines and examples of what such behaviour looks like. For example, you could articulate what sort of things qualify as leadership for a given role, or what tenacity would look like.

It’s useful to get these examples publicised and validated by at least the senior members of your team. This doesn’t have to be a long, drawn out democratic process – part of being a good leader is to understand when autocratic decisions are appropriate. However, getting others involved allows the standards you’re setting to be externally validated and ratified.

Frequency

How often the performance indicator should be measured.

Figure out how often the desired behaviours need to be demonstrated in the appraisal period. This will partly depend on the role and an individual’s stage on their career path.

For example, you can decide that you don’t expect apprentices to show a lot of leadership. This doesn’t mean they may not do so – just that you recognise that they’re young in their career and will generally follow rather than lead. If they show leadership behaviour, then by all means it should be recorded and rewarded – that’s one of the ways to identify high performers for leadership grooming and succession.

Journeymen, however, are expected to demonstrate leadership as a sign of progression. For them, you can decide what leadership means, which behaviours exemplify it, and how often you would like to record it.

The other aspect is how well someone is doing at a particular point. If someone is under-performing, then obviously you have a problem and weekly (or sometimes even daily) measurements are relevant. For high performers who only need to be appraised quarterly, it might be a fortnightly or monthly measurement.

Also remember that making and recording observations requires an overhead in terms of time and effort. This is true in all systems – human or machine – and you’ll need to make a call about how much overhead you’re prepared to bear of your and other people’s time.

Score

The rating system for a performance indicator.

This is can be fairly straightforward or as complex as you want to make it. My advice is to use a simple linear scale from +2 to -2. The negative numbers are required to record instances where the opposite of the desired behaviour was observed. An example of such a scale would be:

| Score |

Description |

| 2 |

Exceeded expectations, went above and beyond |

| 1 |

Met expectations |

| 0 |

Did not demonstrate expected behaviour |

| -1 |

Showed signs of behaviour contrary to expectations |

| -2 |

Clearly behaved against expectations |

The description of each scale gradation aren’t that important, as long as the general idea is understood.

Also, remember to keep it simple. It is quite appealing to extend the scale out both ways, or to do fancy things like make it non-linear. Don’t. Keep it simple, and focus on why the framework is being used rather than the framework itself.

Reasoning

Why a score is given for a particular observation of a performance indicator.

When you record a score, always also record the reason that score was given. Again, this can be as short or as detailed as required. Depending on the frequency and the significance of the observation, I usually add enough detail to give me context and refresh my memory when I come back to it later.

One of the reasons for doing this is that it makes you think about the score you just gave. Sometimes I’ll record a score, write out the reasoning, and then realise that the score wasn’t really an accurate reflection of the commentary I’ve written.

Having comments is also useful when sitting down with someone to discuss their performance.You can have a more meaningful conversation when you are able to provide concrete examples of instances where you observed a behaviour that you want to encourage or discourage.

Similarly, if your environment requires it, these records are also helpful for formal human resource processes. For example, you might need to include evidence for justifying an extra performance bonus, or alternatively, to let someone go for consistent under-performance.

Add a pinch (or two) of discipline

A certain amount of discipline is required to consistently use this framework. There’s no point setting up the attributes for each performance indicator across your teams for each person if you’re not going to stick to using it.

Depending on how many people you need to do this for and how frequently, the best way to do this is to add timeslots and reminders to your calendar. All it then takes is perhaps two or three minutes – sometimes even less – to record a score and the reasoning for it.

Because your team is worth it.

Whoa! I hear you say. That sounds like a lot of work.

That’s right. No one said people management was easy. It’s a responsibility, and if you’re taking it seriously, you need to put a lot of hard work into it. Creating cohesive, engaged and high performing teams and a culture to support them requires a lot of effort. But that’s why you do it. That’s why it’s part of your craft.

I’ll write some more posts soon with examples of usage and the sorts of insights that can be extracted from using such a framework. In the meantime, I’d love to hear about any other tools and frameworks being used for quantifying performance.

Nov 7, 2013 | Management, People Management |

In an earlier post, I talked about using performance appraisals as a tool to have a personalised, growth-focussed conversation with people about their careers within the context of your organisation’s business operating environment.

It is important to ensure that these conversation are well grounded in the opportunities available and the established career paths you have set up for your teams.

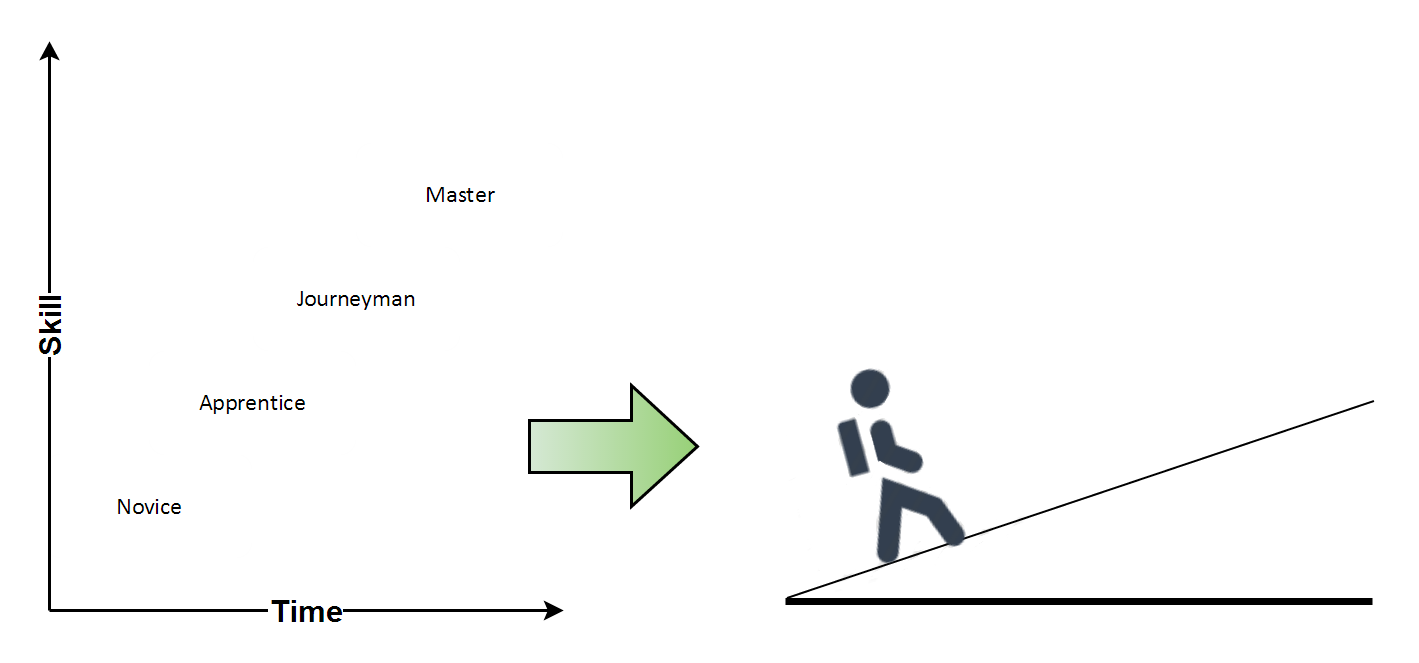

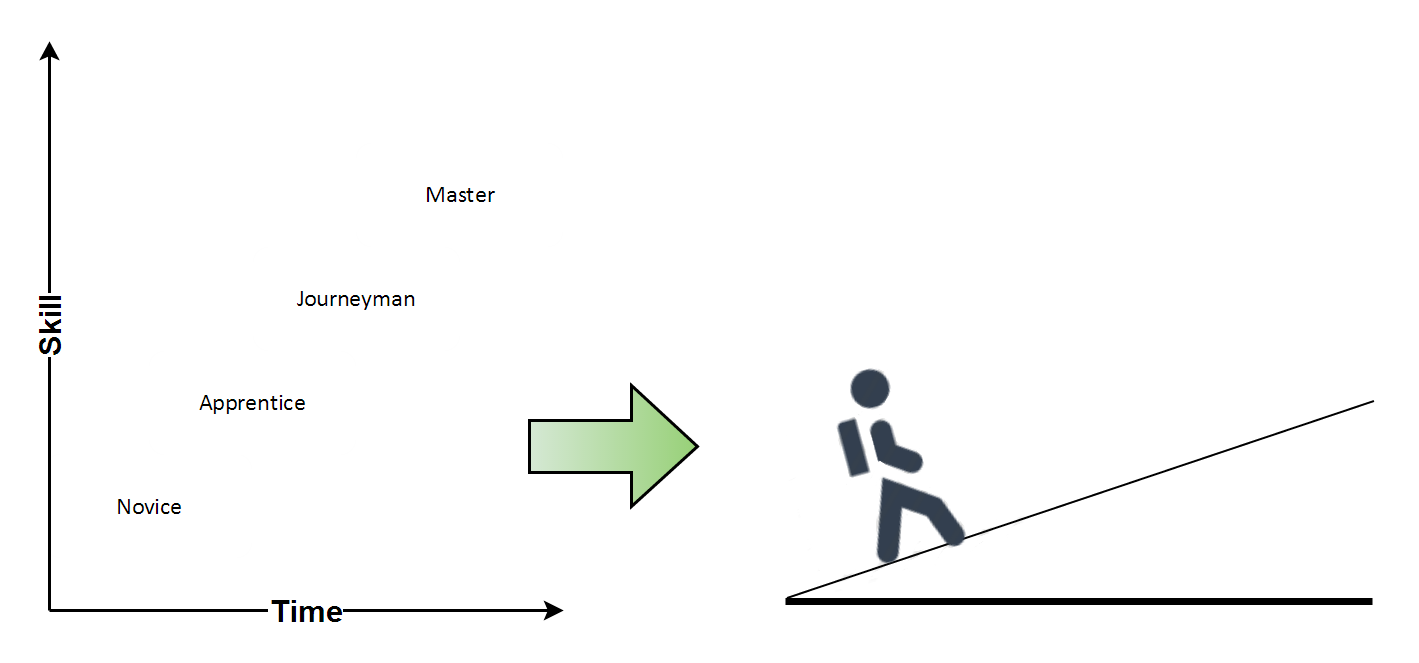

One of the ways I have done this is by adapting the Craftsman Model for Career Management to create a tool that I call Syed’s Slope of Expectations:

It essentially takes the stages along the craftsman journey and plots them on a linear slope, outlining the path one needs to follow to move forward in their career. Remember that this is a model, so it necessarily (over)simplifies things to allow focus on a particular area of analysis.

One of the reasons this works well is that it easy to understand. Everyone gets the metaphor, and it doesn’t require lots of planning or documentation to start using it. You can go out for a coffee and use it to have a casual chat while waiting in in queue for your slightly hot organic weak decaf skim soy caramel latte with extra froth.

How it works

Basically, it can be used to have conversations with individuals and explore one or more of the following:

- Where on the slope they currently are.

- Have they moved on the slope?

- Which direction they’re moving in (or standing still).

- Why do they feel they’re moving in that direction?

- What needs to happen to keep moving forward (or stop sliding back)?

- Is this still the right slope from the last time we spoke?

- If this is the wrong slope, how do we get them to the right one?

This isn’t an exhaustive list. Use these as starting points and go from there. This is an analysis tool, so make sure you ask lots of open-ended and probing questions in a non-interrogative way.

Although it isn’t essential, it also helps to have some sort of career progression framework in place to refer to when having these conversations.

It’s all in the name

When I first called it “Syed’s Slope of Expectations”, it was deliberately meant to be a joke. Everyone chuckled when I first drew it up in a group-wide meeting and explained how it works. But the name has interesting connotations:

The expectations are mine

Potentially the more accurate name is “The Slope of Syed’s Expectations”, since I expect people to put in their best effort at work. If they don’t, then they let themselves, the rest of the team, and the organisation down, and I really want to understand why so I can help them get over it.

It’s an incline

Climbing up, by definition, is challenging. If someone isn’t being challenged, they’re not growing and getting better. Not a good thing. It’s understandable that everyone goes through periods where they just need to consolidate their skills or are going through a major life event outside work. Other than that, they really need to be ploughing ahead.

If you’re not going forward, you’re standing still or sliding down

I really like it when someone identifies themselves in this situation. It requires a keen sense of awareness and contextual understanding, and tells me that I need to invest more time to help this person out. We can explore why a person is feeling this way, whether their perception is just based on some short-term frustration or an actual issue, or how we can find ways to remove impediments from their path.

It’s really about communication

Communication is one of the foundational elements of great people management. Hopefully this tool helps improve yours as you move along your path to becoming a management and leadership master.

I’d love to hear if you use a similar concept, and what your experience with it has been.